Thoughts on Recent JAMA Breast Biopsy Study

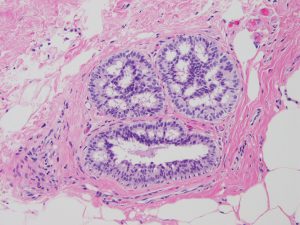

The accuracy of pathology diagnoses of breast biopsy results was recently called into question in the study published in the March 17, 2015, issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). Researchers reported that practicing pathologists incorrectly diagnosed nearly 25% of breast biopsies presented to them in a test study.

The accuracy of pathology diagnoses of breast biopsy results was recently called into question in the study published in the March 17, 2015, issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). Researchers reported that practicing pathologists incorrectly diagnosed nearly 25% of breast biopsies presented to them in a test study.

These findings did not go unnoticed by the national media. On the same date the study was published, The New York Times ran a headline referring to “room for doubt” among breast biopsies with a PBS NewsHour video by the same name. Medscape and other physician-centric websites ran similar articles on the date of publication.

DarkDaily.com has a nice summary entitled “JAMA Report Highlights Inaccuracies in Pathologists’ Breast Cancer Diagnoses”.

In the recent study published in JAMA, overall concordance among pathologists for atypical diagnosis was less than 50%. Overall concordance for DCIS was only 84%. For cases that were completely benign or clearly invasive, concordance was 87% and 96%, respectively. Three reference pathologists agreed unanimously on the diagnosis for 75% (180 of 240) of the cases after the initial independent evaluation.

In this study of pathologists, in which diagnosis interpretation was based on a single breast biopsy slide, overall agreement between the individual pathologist’s interpretation and the expert consensus derived reference diagnoses was 75.3%, with the highest level of concordance for invasive carcinoma and lower levels of concordance for DCIS and atypia.

While medicine remains part art and part science, pathologists generally agree with each other for invasive carcinoma. However, in cases of DCIS and atypia, pathologists agree with each other less often. This may result in over- or under treatment to the patient with diagnostic uncertainty.

While the study itself in this instance has some design flaws not widely acknowledged by the popular press or highlighted in the PBS video in an interview with the lead author of the study, this is unfortunately not new news.

In July of 2010 The New York Times ran an article “Prone to Error: Earliest Steps to Find Cancer” about issues with the diagnosis (or overdiagnsosis and overtreatment) of ductal carcinoma in-situ in a Michigan patient.

Prior to this case, there were numerous reported cases of misdiagnoses of breast biopsies in Canada over several years that were uncovered between 1997 and 2005, going back more than 10 years ago and more cases summarized on this Canadian blog in 2010.

So what can we learn about the most recent news regarding known difficulties and limitations in breast pathology as the criteria exist today for clinically appropriate, reproducible criteria that pathologists and their clinicians can follow for appropriate management options?

What is perhaps most concerning is not that there is confusion in the community about diagnostic criteria for atypia and DCIS, but that there was some confusion among breast pathology experts themselves who community pathologists follow to provide guidance about diagnostic criteria. This is true in all areas of surgical pathology and we strive to create reproducible, clinically significant criteria for all organ systems.

I have heard from several of the pathologists who participated in the study. While they claim to be told the mechanics of the study, there was a general under appreciation of how many “difficult” or “in-between” cases would be included in the study set. The participants also acknowledge that while they were presented a single slide, based on that, the results would be classified with some ambiguity beyond hard “cut-offs” for atypia or DCIS as specific categories. One of the participants claimed slides often arrived late after review from the prior pathologist and time was limited to make their interpretations before having to send to the next pathologists in the study as they shared sets of slides. The same participant claims he never received the last set of slides he was to review and was not provided the expert opinion results after study completion as he was promised.

This may represent another example of pathologists being their own worst enemies, likely not being part of the study design itself, but rather the self-study of themselves. Some pathologist proponents would argue the study design itself was designed to fail, creating a “trap” for pathologists to fall into and it appears we have done our part in that.

Nonetheless, I think given the decades long discussion about issues in reproducibility in breast pathology, we all need to consider what is in the best interests of patients. For some, mandatory reviews of all breast biopsies (just as with prostate biopsies) or all new malignancies or diagnoses of high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus, for example, be performed, as is the case in many practices across the country. There is no substitute for looking at the same slide at the same time with a colleague, particularly if he/she has sub-specialty interests and expertise in that area.

I think this study suggests that mandatory second reviews for all breast biopsies should be conducted in laboratories, pathology groups and departments. It appears that these cases can be problematic and confidence for individual pathologists diagnostic certainty may vary. Streamline QA processes for consensus reviews considering disagreement, even among expert breast pathologists, should become standard of care for the 1.5 million women annually who undergo breast biopsies.

Discussion about whether these should be internal and/or external second opinions and how to meet the needs of patients, pathologists and payers needs to be had to provide safe, accurate, timely and cost-effective reviews for patient management.

The College of American Pathologists and American Society of Clinical Oncology have partnered in the past regarding safe testing in laboratories for ER, PR and HER2 in breast biopsies taking some lessons learned about tissue processing and interpretation and making standardized recommendations to improve reproducibility. Perhaps a similar partnership for breast biopsy interpretation can be implemented for improved consistency and reproducibility for H&E reads as well combined with mammography data and clinical outcomes data.

Lastly, the study makes mention of creation of whole slide images from the study sets used to be evaluated in an alternate study. It will be interesting to see, as is increasingly being demonstrated, if whole slide imaging may be superior to light microscopy for diagnostic concordance in areas of pathology with known intra- and interobserver discordance. Given difficulties in interpretation of breast biopsies, patients may benefit from computer-assisted image analysis applications that may offer greater diagnostic reproducibility.