In my first year as a pathology attending, our pathology department offered a fine needle aspiration (FNA) service for subcutaneous lumps and bumps that were easily accessible by palpation. For the most part we FNA’d palpable breast masses, enlarged lymph nodes and subcutaneous masses. Occasionally we would do thyroid nodules as well. We performed several hundred FNAs a year and read many more that were performed in radiology.

As the day was winding down on Christmas Eve this particular year, I was called to the oncology clinic to see a young female with a history of breast cancer for a “clinically suspicious subcutaneous mass r/o CA”, meaning, exclude metastatic cancer.

As I seem to recall, she was in her late 20’s, had been married for a couple of years and had a child under 1 at home.

The patient and her husband were in the room when I arrived with my cart with my microscope, stains, syringes and needles. I picked up the stamped consent form in the desolate oncology clinic as it was nearing 4:30 on Christmas Eve. I didn’t see the oncologist who had ordered the FNA to discuss the case with him.

Upon arriving in the room, I took a short clinical history, performed a brief physical exam and obtained consent for the FNA. Our cytotechnologists had left for the holiday.

The “clinically suspicious subcutaneous mass r/o CA” was actually multiple masses on the patient’s back and shoulders. Most were firm and immobile, others were softer with a purplish hue on the skin. There was little doubt what they were.

And the patient and her husband knew it. She was weeping. He looked at me with stare and gaze that told me he knew too.

The first pass into one of the firm nodules easily palpable made a gritty sound as I used a needle only technique to aspirate some cells. I am sure my hand trembled a bit as the patient started to cry more openly.

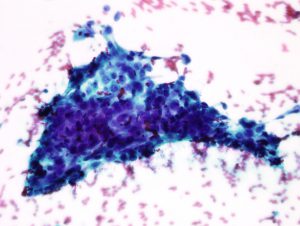

The rapidly stained Diff-Quik slides confirmed what everyone has suspected. There were a sea of poorly differentiated malignant cells.

Despite discussing with the patient that we don’t normally provide a diagnosis as provide that to their physician to discuss with results with them, she asked what I saw. I tried the usual, “we have enough material to process, we are only staining half the slides, we will prep the remainder and provide a report to your doctor as soon as possible approach.” She wasn’t going for it. She knew there would be no slides made on Christmas and the weekend was approaching after that. She asked if I saw cancer cells.

I thought about stepping out of the room at that point to get the patient’s oncologist. They are better at this than I am I thought. In pathology, we give bad news to people all the time but those people are other doctors that relay the message.

It was Christmas Eve. I couldn’t tell her on her child’s first Christmas she had subcutaneous metastases all over her back and shoulders and perhaps elsewhere I had not looked and needled.

There was no leaving the room though and there were no knocks on the door to interrupt me. Come to think of it, none of the other rooms were even occupied when I arrived a few minutes earlier. She likely had the last appointment of the day and it was possibly just the three of us left in the clinic.

How would I exit the room after telling her? Should I tell her or try to convince her a report would be forthcoming shortly to review with her physician? Unfortunately, the couple knew the score before I told them.

I told the patient there were tumor cells from the FNA. They looked like breast cancer cells. I told her I was sorry. The cries became higher pitched and she refused her husband’s attempted consolation. I reached for her hand. She pulled back to wipe her eyes and cheeks.

Just then the oncologist entered the room. I was facing the door. I nodded and he nodded back to me and approached the patient. He put her arms around her and thanked me for coming down on short notice. I nodded again and unplugged the microscope from the wall that was the only thing tethering me to the room at this point. The husband nodded at me as I backed out of the room with the “positive slides” and alcohol-fixed slides and needle rinse in tow.

It was nearly 5 PM on Christmas Eve. There was no wait for an elevator back to the laboratory. Accessioning was closed. I did what I could to leave instructions for the prep tech to accession and finish preparing the slides.

I had had some rough minutes and hours up to this point as an orderly, medical student, resident and attending. There were codes and traumas and children dying of cystic fibrosis and lives lost to leukemia, lymphoma, heart attacks and strokes. But these never seemed to occur on the eve of Christmas before as the attending, the one responsible for making the call and delivering the news. I had only watched before and it wasn’t a holiday in my recollection.

My head was spinning. Why tonight? Why her? Why their family? I couldn’t go home and I couldn’t stay at the hospital. It felt like I was frozen with more questions than answers. Slowly I walked down to the lobby and out a side door into the dark cold air and stared up at the sky, away from the lights of the city and headlights from hundreds getting ready for Christmas.