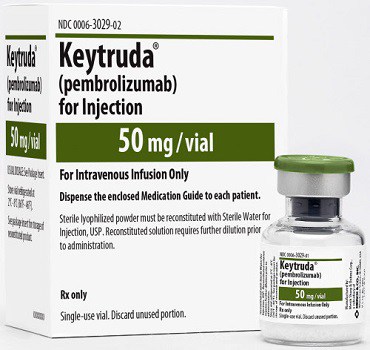

FDA Approval of Immunotherapy For MSI-High or Mismatch Repair Deficient Tumors

Last month the FDA approved pembrolizumab (KEYTRUDA) for adult and pediatric patients with with metastatic or unresectable, microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair deficient (dMMR) solid tumors that have progressed following prior treatment. KEYTRUDA has also been approved fro MSI-H or dMMR colorectal cancers that have progressed following treatment with conventional chemotherapies.

Last month the FDA approved pembrolizumab (KEYTRUDA) for adult and pediatric patients with with metastatic or unresectable, microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair deficient (dMMR) solid tumors that have progressed following prior treatment. KEYTRUDA has also been approved fro MSI-H or dMMR colorectal cancers that have progressed following treatment with conventional chemotherapies.

The immunooncology/immunotherapy story is fascinating.

If my research is up to date, KEYTRUDA, in a short amount of time, has been approved for use in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (complete with the TV ad), classical Hodgkin lymphoma, advanced melanoma, MSI-H tumors, head and neck squamous cell carcinomas and advanced urothelial bladder cancers.

Nivolumab (OPDIVO), also in a short amount of time, has been approved for advanced non-small cell lung cancer, classical Hodgkin lymphoma, advanced melanoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, advanced renal cell carcinoma and advanced urothelial bladder cancers.

However, this last approval is the FDA’s first tissue/site-agnostic approval.

Until now, the FDA has approved cancer treatments based on site or cell of origin – i.e. breast, lung, colon, prostate, etc…Now patients have an option for a drug based not on the site or histology of the tumor but rather on a biomarker.

The approval was based on data from 149 patients with MSI-high or MMR-deficient tumors, 90 of whom had colorectal cancer. Fourteen other cancer types comprised the remaining patients.

In 135 patients, tumor status was determined prospectively by either an investigational polymerase chain reaction test for MSI-high tumors or by immunohistochemistry tests for MMR-deficient tumors. In 14 patients, MSI-high tumor status was determined retrospectively.

MSI-high or MMR-deficient tumors are most commonly found in endometrial cancer, colorectal cancer (up to 5% of metastatic patients), and other gastrointestinal cancers. But these types of tumors have also been identified in genitourinary cancers, breast cancer, thyroid cancer, and others.

Common immune-mediated side effects associated with pembrolizumab that have been reported include colitis, hepatitis, nephritis, pneumonitis and endocrinopathies.

This is exciting news for patients for previously hard to treat metastatic tumors that have progressed following conventional chemotherapy and/or unresectable tumors, based on a immunohistochemistry biomarker or PCR test.

But I think this is more mixed news for the future of pathology.

On one hand, given the number of colorectal and endometrial cancers, as well as potentially the request from oncologists to test breast, thyroid, genitourinary cancers and others from MSI-high status, we will be performing a lot more of these tests.

On the other hand, pathology has prided itself on morphology and classification of disease. Predicting tumor biology and patient outcome with our morphologic skills and determining the tumor size, nodal status, extent of resection, lymphvascular space presence of absence and metastatic deposits of tumor cells summarized in reports using agreed upon “TNM” staging to guide therapy has been the mainstay of pathologists.

Immunohistochemistry has been routine in anatomic pathology laboratories to classify and attempt to determine if tumors would respond to particular therapies or to try to predict cell of origin or tumor biology.

Increasingly, the collection of tissue has been less about the morphology but about the biomarker and mutational status. Looking at EGFR, kRAS or BRAF mutations, to name a common few with specific therapies in appropriate patients that could maximize the “kill factor” of the tumor cells without destroying normal tissues as well. Multi-gene panels made their way into the cancer care continuum only to be upended by PD-L1 testing and the use of nivolumab and pembrolizumab in patients with PD-L1 positive tumors (without EGFR or ALK mutations) and so forth.

Still, adequate tissue had to be obtained to classify the tumor as small cell or non-small cell and appropriately test for PD-L1. One cannot get through a pathology lecture at a CME meeting this days without a schematic of the PD-1 receptor on an activated/re-activated T-cell. At one point, BRAF status in patients with advanced melanoma was important but now indications include both BRAF+ and BRAF- patients.

Now we have the approval of a drug whose use may be indicated regardless of tissue histology or tumor site, based upon DNA mismatch repair pathways and our ability to detect. As a subset of colorectal, head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, non-small cell lung carcinomas and others, previously approved for PD-L1 monoclonal antibody therapy, the use of testing for mismatch repair deficiencies is exciting in that many laboratories already have this ability and can help more patients than previously thought.

But is the science of morphology and classification a passing art?

Will pathologists continue to be regarded as “a physician who performs, interprets, or supervises diagnostic tests, using materials removed from patients, and functions as a laboratory consultant to clinicians, or who conducts experiments or other investigations to determine the causes or nature of disease changes”?

Or will be regarded to carry out part of this role as in diagnosing a core biopsy from an unresectable or metastatic tumor as “MSI-High tumor present” to guide therapy?

How long will it be before we add these drugs to the water supply like fluoride?

More on this in a future post on my “Thoughts on ASCO 2017” (after ASCO ends to see if there is any more potential opportunity for additional immunohistochemistry testing, regardless of tissue/cell of origin or site).