Physician Burnout: Is it Real and What is the Cause? Part 1

I don’t recall where I read it but I do recall when. In a page of a book written by a physician, he lamented there are three things that can change a person’s life forever (perhaps not in this order but as I recall it): Going to medical school, joining the Army and giving birth to a child. When I read it I was working as an orderly at a hospital in mid-Michigan waiting to go to medical school and join the Army to pay for that medical school. Since I am not a seahorse or a few other non-mammalian species, the possibility of giving birth was out of the question but the other two were about to commence.

I don’t recall where I read it but I do recall when. In a page of a book written by a physician, he lamented there are three things that can change a person’s life forever (perhaps not in this order but as I recall it): Going to medical school, joining the Army and giving birth to a child. When I read it I was working as an orderly at a hospital in mid-Michigan waiting to go to medical school and join the Army to pay for that medical school. Since I am not a seahorse or a few other non-mammalian species, the possibility of giving birth was out of the question but the other two were about to commence.

I am not sure where going to medical school and joining the Army rank on my list of life stressors. My first year in college was tough since I didn’t learn how to study and needed to. The death of my father still sticks with me as a significant event with repercussions today almost 10 years later. Internship year as I have written before (see: The Midnight Menu), was likely the hardest and in some ways, the best year of my professional life to date. Certainly going to medical school and working as an Army physician were a part of that.

In either case, you learn quickly parts of your life are not your own. The pre-medical curriculum, preparing for the MCATs, applying to medical school, the interview process and then eight hours of didactic lecture daily followed by hours of study for two years after organic chemistry, getting through the weeks after the MCAT when you think you bombed, to borrow money to go to the interviews. The process gets repeated by tens of thousands yearly.

In either case, you learn quickly parts of your life are not your own. The pre-medical curriculum, preparing for the MCATs, applying to medical school, the interview process and then eight hours of didactic lecture daily followed by hours of study for two years after organic chemistry, getting through the weeks after the MCAT when you think you bombed, to borrow money to go to the interviews. The process gets repeated by tens of thousands yearly.

Organic chemistry seems to be the great filter. A lot of pre-law and pre-dental and business majors are born out of organic chemistry, or their inability to complete organic chemistry and not having the pre-requisite necessary for medical school.

Then, you get to work on the wards after two years of lecture halls for another two years, if you thought 16 hour days were bad, it can and does get worse. Then, you get to interview for internship/residency, and if successful, match into a program that is funded by Medicare with a guarantee for low wages and long hours.

But surveys done by organizations that do surveys on this show physicians would do it all over again. And the same medical school and residency in more cases than not. In some cases, they would choose a different specialty (like pathology if they had to do it over), but not a different profession.

But surveys done by organizations that do surveys on this show physicians would do it all over again. And the same medical school and residency in more cases than not. In some cases, they would choose a different specialty (like pathology if they had to do it over), but not a different profession.

But now I am seeing more and more on “physician burnout” which I wasn’t going to write about until I saw a piece co-authored by the CEOs of Mayo Clinic and Cleveland Clinic among other healthcare executives and physician healthcare executives. With Mayo and Cleveland Clinic having a physician CEO, these organizations know a thing or two about not only practicing medicine but I think perhaps understanding physicians who practice medicine many floors below the C-suite. And these folks claim physician burnout is real.

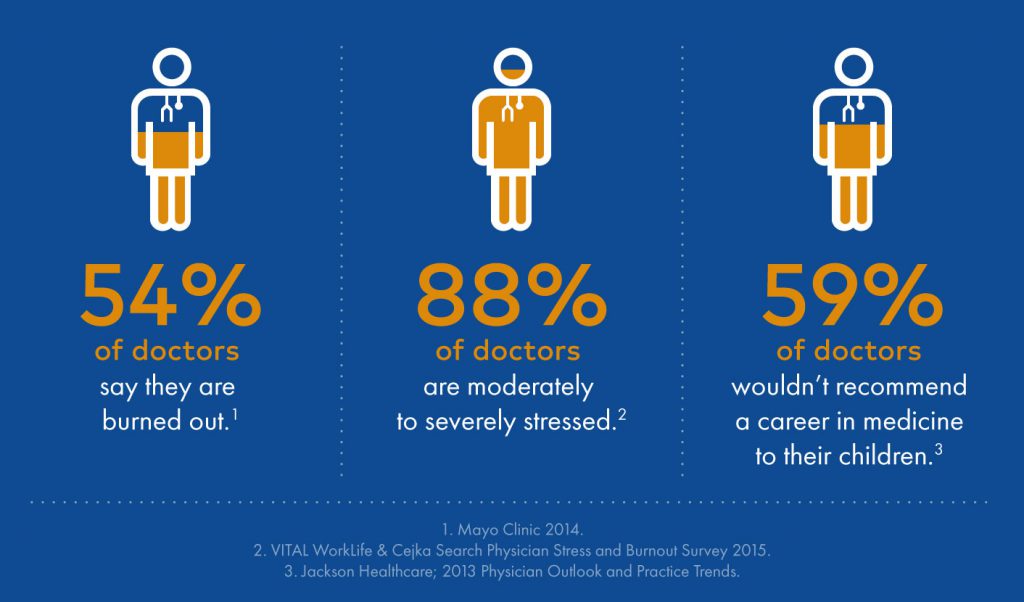

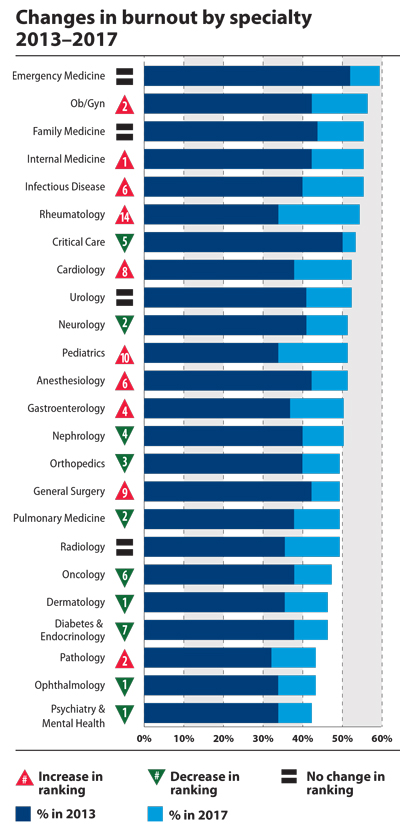

In a study published by Shanafelt and colleagues in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings, the authors conducted surveys of physicians in 2014 and compared those to results in 2011. They reported that 6880 of 35,922 surveys (19.2%) returned showed 54.4% (n=3680) physicians reported at least 1 symptom of burnout in 2014 compared with 45.5% (n=3310) in 2011 (P<.001). Satisfaction with work-life balance also declined in physicians between 2011 and 2014 (48.5% vs 40.9%; P<.001). Substantial differences in rates of burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance were observed by specialty. In contrast to the trends in physicians, minimal changes in burnout or satisfaction with work-life balance were observed between 2011 and 2014 in probability-based samples of working US adults, resulting in an increasing disparity in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians relative to the general US working population. After pooled multivariate analysis adjusting for age, sex, relationship status, and hours worked per week, physicians remained at an increased risk of burnout (odds ratio, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.80-2.16; P<.001) and were less likely to be satisfied with work-life balance (odds ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.62-0.75; P<.001).

This is an alarming trend and suggestions in the literature since this paper was published suggest the trend in physician burnout, a dissatisfaction in work-life balance will continue to increase.

But why now? Did Hippocrates or Sir William Osler or Harvey Cushing or William Halsted or the Brothers Mayo recognize this in themselves of their colleagues?

Is it increased regulations? Payment issues? The dreaded EMR? Lack of independence within larger healthcare networks?

In part 2 will address what I think the important causes and the implications for patient care and physicians alike.