The news has just broke that Thomas Duncan, the first Ebola patient to be discovered in the United States, has died from the virus. The whole world is finding out details about a man that are probably none of our business. One of the points of the story that caught my eye: the patient reportedly mentioned to a triage nurse that he had recently travelled to Africa. Of course, the information wasn’t communicated adequately to the team, and us Monday morning quarterbacks are assigning blame, rather than fixing the problem.

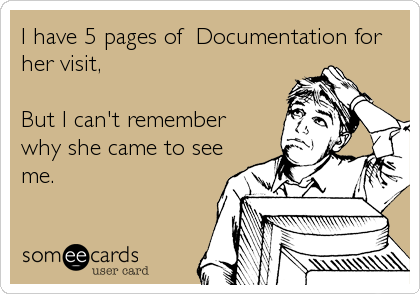

We’ve all seen (and probably used) templates or pre-populated reports. And we’ve seen the templates used in primary care clinics, emergency departments, consultation services, etc, that contain massive amounts of data. Sometimes the template isn’t even completed, so we read something like “bowel sounds were present/absent; the abdomen was soft/distended/tender”, etc. Some of these templates and electronic medical record (EMR) forms have hundreds of fields. How does a human sort through all of this data, much of it mandatory, in order to find out what is significant?

I’m wondering if it’s possible that the “recent travel (yes/no)” box on the Dallas patient’s triage form was present in the background of a sea of data. “Do you feel safe at home”, “when was your last tetanus shot”, “would you like to talk to someone about organ donation”, “do you have a living will or healthcare proxy”, “do you have allergies to latex products”, etc, could have desensitized the chart reader to the presence of a “yes” in the travel question box.

Obviously, electronic forms weren’t meant to replace a good history and physical, but I think it’s possible that they may be getting in the way of our ability to sort out what’s important and what’s not. Have you ever read a pathology report (especially a templated one) and tried to figure what exactly the diagnosis is? Have you ever been called by a primary care physician wanting an explanation of your report?

Isn’t it time that we put some thought into how we use electronic systems for documenting patient care?

I was confused when I first stepped in a physicians office how many forms I have to fill out. It even got more complicated when I changed to a specialist that he uses different forms. I was not used to the circumstance that there is no connection within physicians office, Hospital or specialist to share this important information of patients history. Like Thomas Duncan who lied in the paperwork for the immigration to the US, people lie while filling out questionnaires to gain access to medication or just can’t remember. A central shared database accessed with a Picture ID of the patient to receive a temporary copy of patients history records and update this central records when finished. If there would be a central shared database the only question that comes up in an office visit would be – where does it hurt?