Will Digital Pathology Retire the Microscope?

Courtesy of GE Reports: Will Digital Pathology Retire the Microscope?

Courtesy of GE Reports: Will Digital Pathology Retire the Microscope?

Pathologists are doctors and scientists who study tissue, blood and other biological specimens to find the cause of illness and a route to treatment. Many of them still wield a microscope as their main weapon. They load it with a sample slide, analyze the contents through the eyepiece and dictate their findings to a voice recognition system or an administrative assistant who transcribes them into a report.

But do it dozens of times a day and the job can become a pain, literally. “Every time I reach for a new slide, I have to take my eyes off the lens and check the forms for that case,” says Ian Cree, a pathology professor at Warwick Medical School in Coventry, UK. “You can get a sore neck from hours at the microscope.”

This traditional way of studying samples is now making researchers like Cree wonder whether it’s time to put the microscope away for good. Two years ago, Cree and his team started testing a new digital system that allows them to scan in images of tissue slides and patient histories, attach matching barcodes and upload everything to a massive computer database. Cree now views his samples on a computer monitor and controls their flow with his mouse.

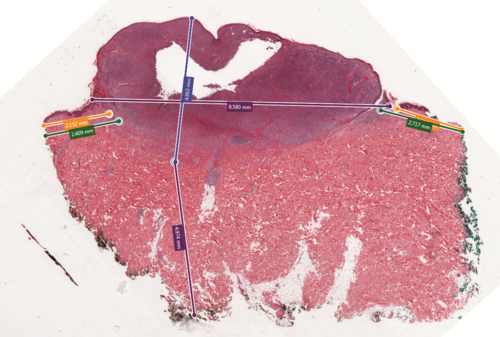

The picture to the left shows how Omnyx’s Image Analysis Application can help with measurements for Dako HercepTestTM, a test commonly used by pathologists in assessing treatment options for breast cancer patients. Top image: Skin melanoma showing digital measurements of Breslow’s Depth and distance to margins.

The system is efficient in other ways, too. After biomedical scientists scan the slides, which hold prepared biopsied tissues some 5 microns thick, the samples don’t travel to Cree’s desk as they once did, but instead go straight back to storage. This makes it easier to preserve and keep track of slides while their images are viewed by the pathologist to find the diagnosis.

The technology allows one pathologist to study around 150 slides a day, increasing efficiency in the lab by about 13 percent. “Digital pathology puts everything directly on the screen in front of you, including the paperwork,” Cree says. “Everything is linked and I can even collaborate with my colleagues without stepping out into the corridor. It’s much quicker and better for everyone, including the patient.”

The system in Cree’s office is called Omnyx Integrated Digital Pathology*. It was developed by Omnyx LLC, a joint venture between GE Healthcare and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center formed in 2008. Omnyx takes advantage of the power of the Industrial Internet, connectivity and data analysis. It could allow doctors to reach beyond hospital walls to create global “pathology networks” that could be global. “We can connect doctors in rural and underfunded hospitals with pathology experts,” says Omnyx CEO Mamar Gelaye. “The technology helps eliminate access as a variable in quality of care.”

Similar Big Data systems are already helping doctors in Sweden to analyze X-rays images of rural patients and improving diagnostics in Washington State.

Omnyx first scans samples with a high-resolution camera and stores the images in a digital archive. Pathologists can access the archive in real time and pull up the desired samples.

The system can be easily scaled up from just one lab to a hospital or even an entire healthcare network. Doctors can use it to collaborate with peers and specialists, improve the accuracy and speed of diagnosis, and quickly obtain second opinions.

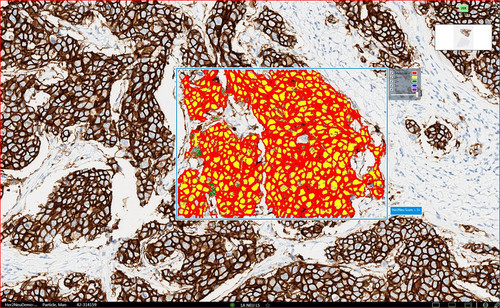

Once Omnyx has gathered enough data, the system could also help pathologists to analyze the data to seek hidden correlations. “The human eye is extremely good at looking for patterns on a slide,” Cree says. “But we are very bad at determining how much of something is on it. That’s where digital pathology adds value for the patient.”

There are, for example, nine grades of prostate cancer tumor. The grade a doctor gives a tumor determines whether a patient receives radical surgery or a more conservative drug treatment. But Cree says that pathologists are about 60 percent successful in identifying the right grade when they use only a microscope and their eyes.

Machine vision and software analysis could improve the odds. “It may be that in the future we find the optimum cut for radical surgery is a tumor grade 4.3 and above, rather than 4, so that we are able to refine our advice and offer a more individualized level of care to patients,” says Dr. David Snead, the pathologist who leads the Omnyx implementation at Coventry and Warwickshire Pathology Services.

The Coventry team has used the new system to study samples from 300 patients. They are now in the middle of a 10-month-long validation study that will include 3,000 cases. The team will compare results generated from Omnyx versus to those using only a microscope to ensure there are no discrepancies.

“We know pathology will evolve, and our solution is committed to stand ready for that transformation,” says Omnyx CEO Gelaye: “We want to use information technology to bring patient pathology cases to the right pathologist for the right diagnosis at the right time.”

Source: GE Reports